Organic Record Keeping

Organic Record Keeping, with a Farmer and an Inspector

By Sam Oschwald Tilton

OATS Training Specialist and an Organic Advisor at Glacial Drift Enterprises

Published December 16th, 2025

Organic record keeping is not a topic I have expertise in. To be honest, it’s always been a little intimidating to me, and I know some farmers feel the same way. However, organic record keeping is a defining part of growing organic crops and capturing the organic price premium. With technology progressing at a brisk clip, there are new ways for farmers to keep their organic records. Some farmers like to do their organic paperwork themselves using their own record keeping systems. Others use a record system designed by someone else, and some prefer to hire an outside advisor to make the whole process easier and take a lot of it off their plate. To understand all these options, I was happy to welcome two guests onto the Organic Advisor Call Series this summer who had great perspectives to share. Matthew Fitzgerald is a Minnesota grain farmer and advisor, and Mallory Kreiger is a former organic inspector and is currently an organic certification consultant. Between their wide experiences, we learned a lot about record keeping options and best practices for organic farmers.

"There are so many different systems to keep organic records, and I feel like whichever fits a farmer well is the best for them. But all effective record keeping systems, whether it is a notebook in the truck or a consultant’s spreadsheets, will share some traits."

– Mallory Kreiger

Mallory and Matthew stressed the crucial basics of record keeping. There are a few elements that every effective organic record keeping system will have. The NOP does not dictate how to keep organic records, only that records should be accurate and complete. It’s important that farmers choose a system that they like, understand, and will actually use. Mallory shared her experience of visiting with a farmer in the office during an inspection, asking for documentation, and the farmer pulling out several cross-referenced handwritten notebooks. “That was just fine. All the information was there, it was clear, and it was verifiable. Not the way I would do it on my farm, but it worked for that farmer.” Any organic record system should be practical for the farmer, complete, and auditable on-site. For example a shoebox full of receipts and sticky notes could be practical, it could be complete, but it would not facilitate an effective audit.

The next crucial element of record keeping is that it provides traceability from seed to sale. Matthew explained that the goal here is being able to trace any input or crop forwards and backwards, or, “being able to tell the full story of a crop.” A farmer’s records should allow them to trace the crop from its arrival on the farm as seed, to planting, raising it (including any inputs applied), harvest, storage, and sale. On his farm, Matthew uses a system of field ID numbers and crop lot numbers so that each soybean can be traced throughout its time on the farm and with each field operation. The goal is to have a continuous connection, or chain, of records through all parts of production and sales. At any point in the production cycle, an inspector wants to be able to trace in the records where a material or crop came from and where it went.

A few key records can help with traceability. Seed tags and lot numbers show where seed came from. Activity logs for all operations document things like planting, weeding, scouting, harvest, and equipment cleanouts. There might be further documentation needed at certain steps beyond activity logs. For example if a custom harvester was used, then documentation of their equipment cleanout in the form of an affidavit must be received and recorded. Once grain is sold, the bill of lading should record what bin the grain was pulled from. The bill of lading will then connect to a record of filling the bin, which records which fields contributed grain to each bin. You can see how traceability means being able to look forward and backward from any point in the records.

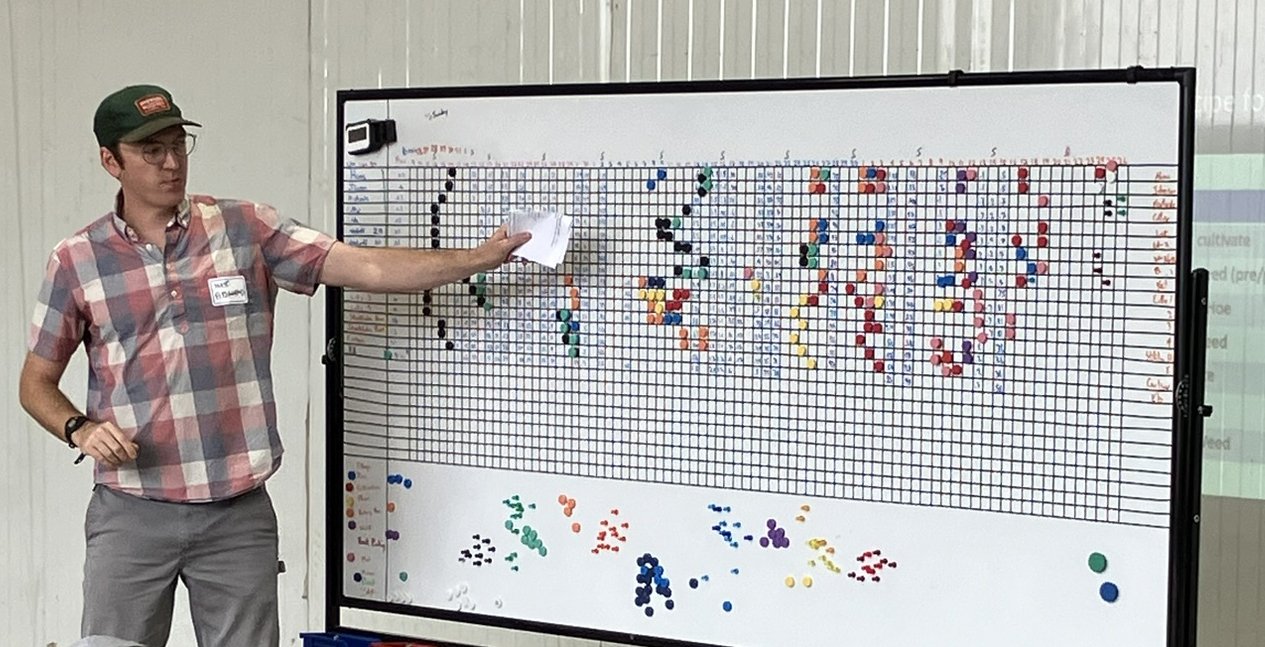

With those record keeping basics in mind, there are several types of record keeping systems that are practical, complete, and auditable. Analog, simple methods can work well. These would be methods like notebooks with seed tags, bills of lading, and other documentation stapled into the appropriate page. Wall calendars can also work for a paper-based system, as long as everything is recorded, since, as Matthew says, “if it isn’t recorded, then it didn’t happen.” On his farm, Matthew used a large whiteboard kept in the shop where all field activities were planned and recorded. It made it easier for employees to keep records of their activities. He would take a photo of the whiteboard at different times during the season. Those photos, along with well-organized documents of things like seed tags and bills of lading, were an effective system on his farm.

There are other options that incorporate more technology. While these may be a little harder to learn or set up, the technology automates a lot of the recording. For example, some farmers still rely on paper to record field activities, but supplement them with photos saved in the cloud. Because photos are automatically time-stamped, they can be sorted by date and serve as a good complement to paper records. Similarly, photos and other smartphone notes can be geotagged, which automatically records the location where information was recorded on the phone. This can help document activities like equipment and bin cleanouts. Data from other devices can also be captured for organic records, like from a combine’s yield monitor. These are all hybrid approaches that combine analog and digital records.

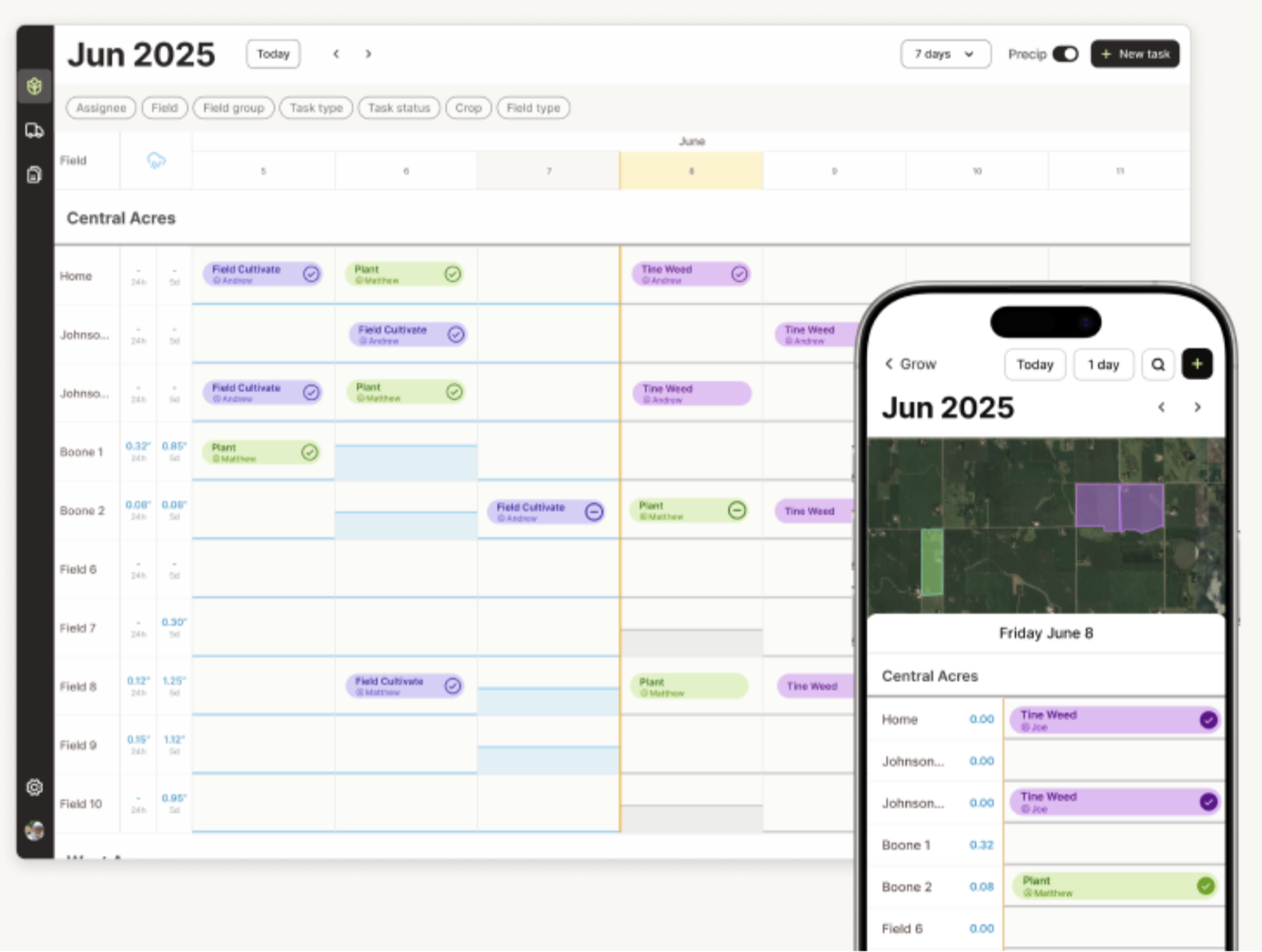

For those farmers who want to be completely digital, there is software specially made for organic record keeping. Matthew has incorporated lessons learned from his detailed whiteboard, and created a program called FarmFlow that farmers can use on their computers and phones in the field. It is a software platform that allows farmers to keep all records on their phones, through notes and photos that get organized in the program and from which reports can be generated. If you are interested in FarmFlow, you can find more information on the website. Instructions for making Matthew’s giant whiteboard are available there as well.

Record keeping systems can vary with each farmer’s personality. Regardless of the system, there are some common record keeping mistakes that Matthew and Mallory observe. Yield data can be a common gap. A bill of lading when grain is sold off the farm is not proof of yield - that would be skipping a few steps. Rather, farmers need to be sure to record field-level yields as grain is coming out of the field, and they should know where the grain came from that is filling each bin. Another gap commonly seen is not accounting for shrinkage. When an inspector does a mass balance audit, they are verifying this equation:

Beginning Inventory + What was Produced - What Left the Farm = Ending Inventory

Common Sources of Shrinkage

Figurative shrinkage – For example, a farmer had a layer of sprouting wheat at the top of the bin. They removed this low-quality wheat but did not record how much.

Literal shrinkage – Grain can shrink substantially during drying, and it will appear as though some grain disappeared. A farmer must account for that shrinkage.

On-farm feeding – If grain is pulled out of a bin for feed, it must be recorded; otherwise, the total would be off.

Purging – In split operations or with custom harvesters, some equipment, like combines and augers, need to be cleaned out (“purged”) with organic grain. Once used for purging, that grain is no longer organic and needs to be accounted for.

When losses are recorded properly, the inspector can reconcile the amount produced with the amount sold and the ending inventory. During a mass balance audit, this helps verify that everything coming in and going out is documented and the math works out.

Record systems and planning are important, but at the end of the day a farmer’s mindset can have just as much impact on the quality of their records. When we don’t enjoy something or don’t see the value, we are often less likely to do it. Organic record keeping is no exception. I commonly hear newer organic farmers lament the time and effort required for their organic record keeping. But Matthew has a different take, “You just have to have a positive mindset about record keeping, to appreciate why we are doing this. And that ‘why’, for me at least, reduces the frustration or the eyeball glazing that happens."

For Matthew, when he connects record keeping with the organic certification it supports, it changes his whole experience. His mindset about it changes and his records become a priority and a point of pride. “Records make me organic, and being organic drives value to my farm revenue and to my customers.” Organic records aren’t just paperwork; like fertilizing or cultivating, they add value to a farm’s crops and keep the system running smoothly.

Want to hear the full conversation with Mallory and Matthew?

Watch “Organic Record Keeping with a Farmer and an Inspector” from our 2025 Organic Advisor Call Series on YouTube.

Listen as a podcast for a closer look at organic record keeping.